The person behind Matsusaka City Tourism’s official Instagram (@discover_matsusaka) brings you an inside look at the Matsusaka Castle Ruins.

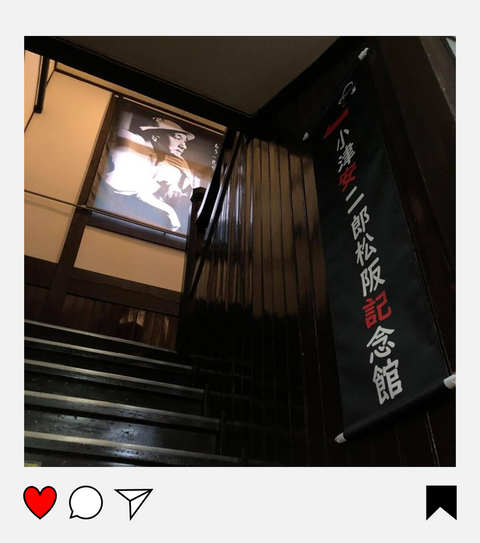

So, Where is Matsusaka? And What’s There?

Matsusaka is just about the middle of Mie Prefecture, and everyone on their way to the Ise Grand Shrine passes by (although not everyone stops in). Which means, a lot of people know about Matsusaka beef, but not everyone knows about the city itself. Too bad, right?

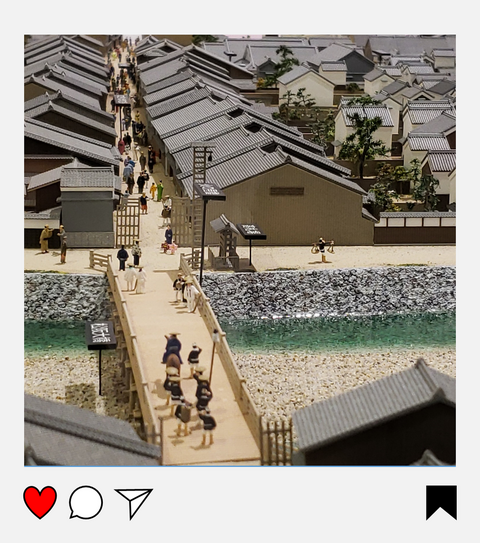

But back in the day, it was a happening spot. People would make it a point to stop on their way to the Ise Grand Shrine, and it’s situated where a number of roads to Ise come together. It flourished as a good place to stop and rest. In the busy times, apparently about 1/6 the population of Japan (5,000,000 people back then) would visit the Ise Grand Shrine every year. Now, it’s more like 20,000,000 a year—which is basically the population of Osaka and Tokyo descending on the Ise Grand Shrine. Crazy, right? So much for social distancing.

Now you might be thinking: “So that means people in the Edo period (1603-1868) were eating Matsusaka beef, right?” Unfortunately not. Turns out, we didn’t start eating beef in Japan until the Meiji period (1868-1912). Historically, cows were important in Japan as working animals, and the added influence of Buddhism made beef a taboo from the Nara period (710-794) onward.

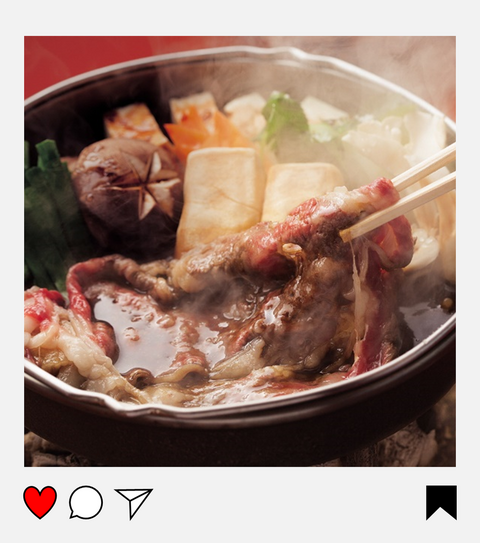

But times change. The Meiji government wanted to both strengthen its people and keep foreign relations smooth, so it promoted eating meat; when the Meiji Emperor took the initiative to get rid of the taboo, it effectively stimulated a culture of meat eating. The only thing is, the beef back then was tough and had a strong smell, so grill it, boil it, fry it, and it still didn’t taste good.

But enter the magic of Japan’s traditional condiment: Miso! With the powers of miso, we overcame beef’s toughness and smelliness, and the Meiji Era of Enlightenment also saw a boom in beef hotpot. And as people figured out more ways to eat beef, we saw the birth of sukiyaki. Over time the quality of the beef got better, and we developed what we now know as wagyu—Japanese beef. And one of the ultimate forms of that is Matsusaka beef.

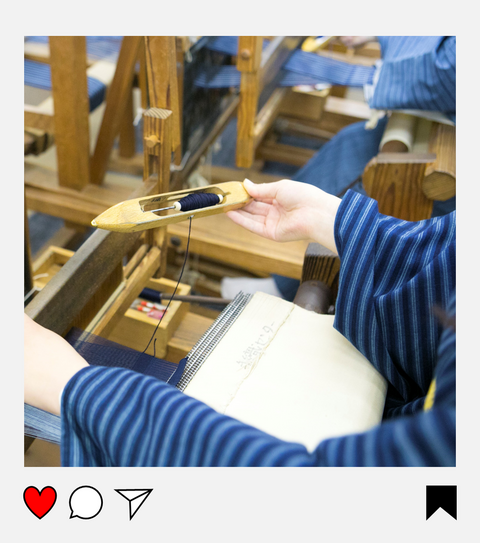

I’m digressing a bit, but to understand Matsusaka, we had to talk about the beef. And I really want to go into the hit of the Edo fashion world, Matsusaka cotton. But we’ll save that for another time.

If you want to know more about Matsusaka beef, check this out:

“Wait…why was a Matsusaka product so popular in Edo? You’ve gotta tell me!” If you’re thinking this, click here for more:

Matsusaka Castle Ruins

Alright, let’s move on. What’s in Matsusaka? That’s right, the National Historic Site, “Matsusaka Castle Ruins”! It’s counted among the 100 best castles in Japan.

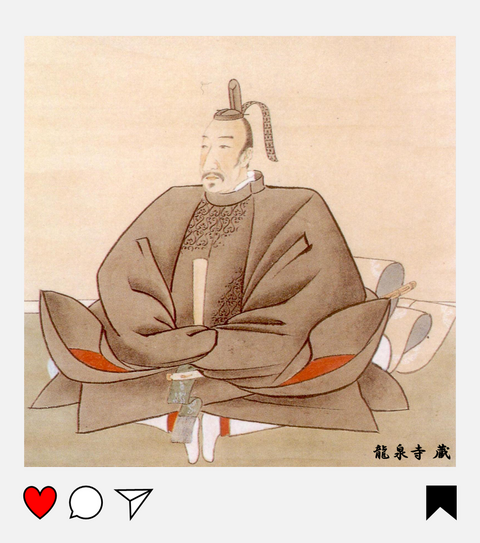

I’m going to have to take our conversation back in time a bit: Matsusaka Castle was built by Gamo Ujisato, a military commander in feudal Japan. He was a famous warrior, lover of tea, culture aficionado…he’s got a fascinating story, but I’m supposed to be telling you about the castle…

But for those of you interested, you can find out a little bit more about his exploits here:

Anyway, back in Gamo’s hometown Hino in Shiga Prefecture is a place called “Wakamatsu no Mori,” which means “Forest of Young Pines.” He took the “Matsu” from “Wakamatsu,” and borrowed the “Saka” from his boss Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s “Osaka Castle,” and named the area “Matsusaka.” Speaking of which, there used to be two pronunciations, Matsusaka and Matsuzaka, but in 2005 the government standardized it as Matsusaka. Weird to look back and think we used to have two ways to pronounce it.

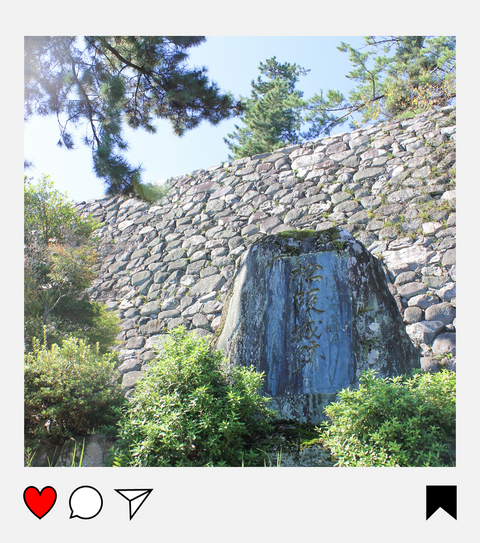

Back to the castle—or rather, the lack of it. That’s right, all that’s left now are the “Matsusaka Castle Ruins.” The castle tower was destroyed by powerful winds in 1644, most of the other buildings were later destroyed by fire (we think? It’s not totally clear), and all that was left by 1881 were the stone walls.

So, What’s There to See at the Matsusaka Castle Ruins?

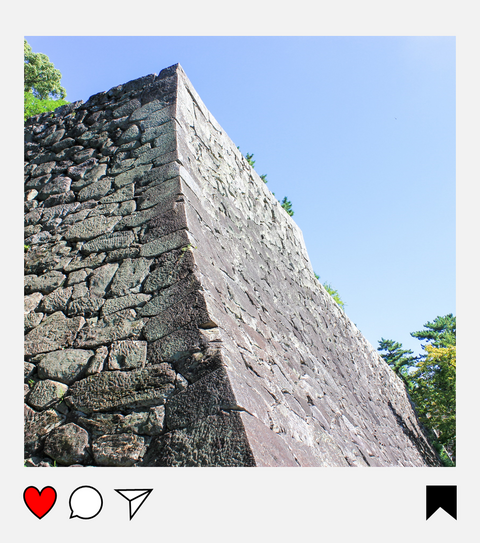

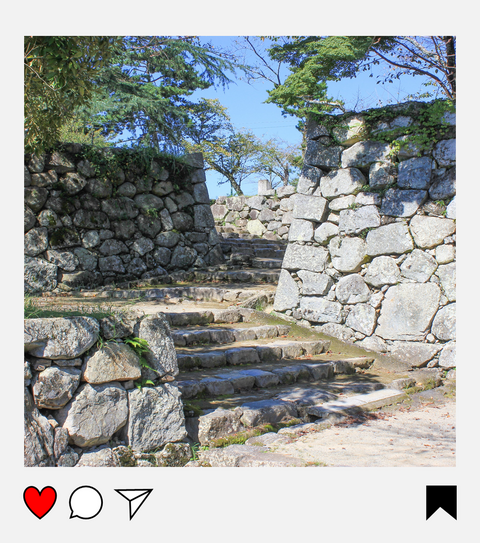

The thing to see at Matsusaka Castle Ruins is the castle walls! They’re famous as some of the most magnificent castle walls in Japan, and people come here just to check them out.

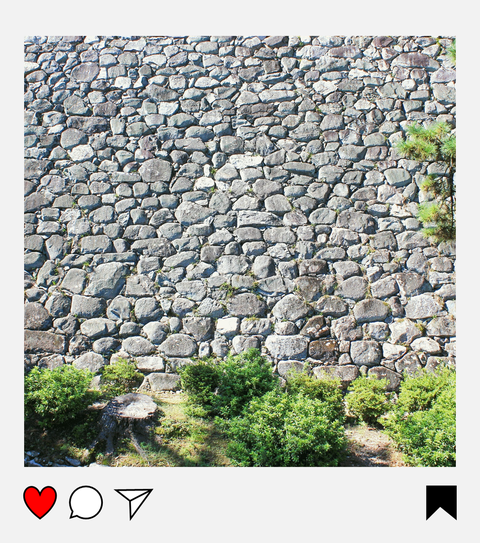

The majority of the walls were built using a technique called “nozura zumi” (explanation below), and there was a period of renovating castle walls in the Edo period (1603-1868), where they used “uchikomi hagi” and “sangi zumi” (also see below). The walls were apparently built by a legendary group of specialists from Omi (now Shiga Prefecture) called the Anoshu, who were thought to have built about 80% of early-modern Japanese castle walls.

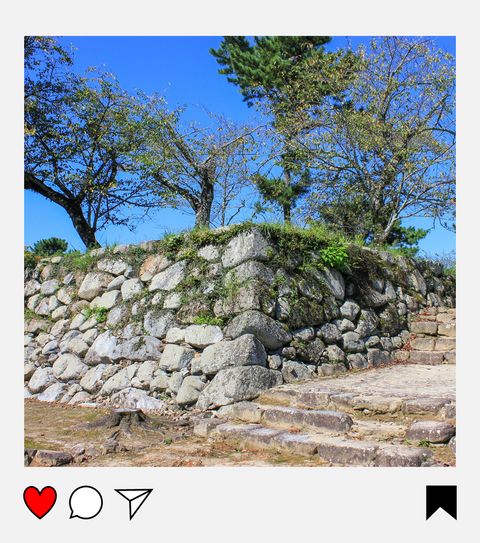

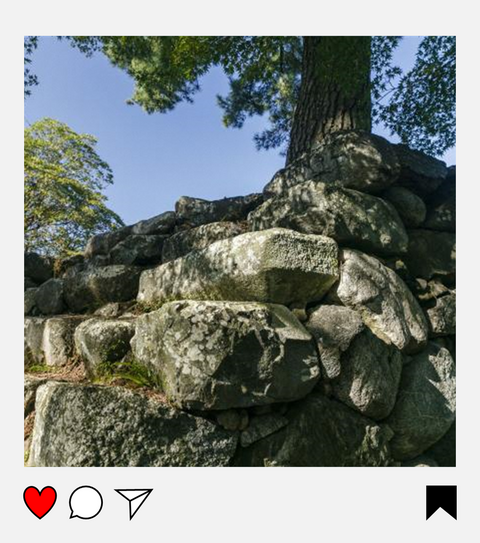

Nozura zumi was a building technique where the stones weren’t cut, they were kept in their natural shape and stacked together. Up where the castle tower used to be, you can tell the walls are just natural stones put together, and they’re a great of example of nozura zumi! These walls look the same as when they were built, and hard-core castle fans get really excited over them.

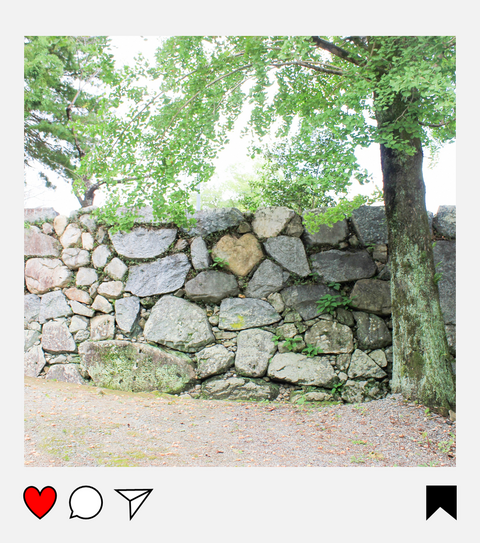

Times progressed a bit, and people started to process the stones to make them easier to stack. The uchikomi hagi technique works the stones so that there are fewer gaps—although the fitting isn’t flush—and fills those gaps with tiny stones.

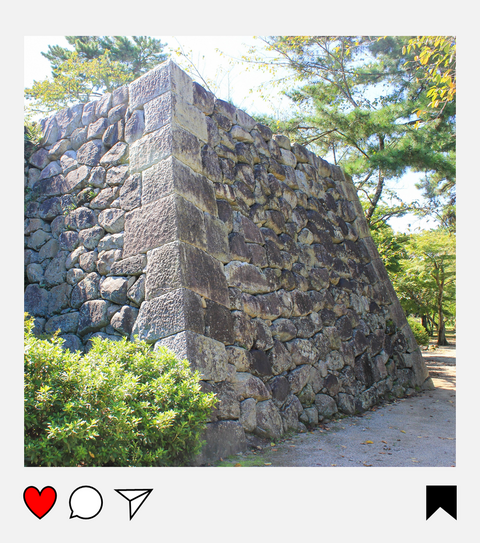

You can see sangi zumi at the corners of the walls, where long rectangular stones are stacked in a long-end-to-short-end alternating pattern. Even though this technique was used in many castles, you can feel the different stages of history based upon how well the stones were processed. Check out the corners of other castle walls and compare them if you get the chance!

I also want to point out something about the actual stones here. It takes a lot of rocks to build a castle, so it is said workers had to gather stone from the outskirts of Matsusaka when they were building. Mixed in with other rocks are the lids from stone caskets dating back to the Kofun period (250-538 CE). You can still see them today.

There’s even a heart-shaped stone. The builders weren’t trying to make the castle cuter, it’s actually something called “inome,” or “Boar’s Eye,” and it’s a both charm against evil spirits, and a way to bring prosperity that you can find in some traditional Japanese architecture. Try to find it!

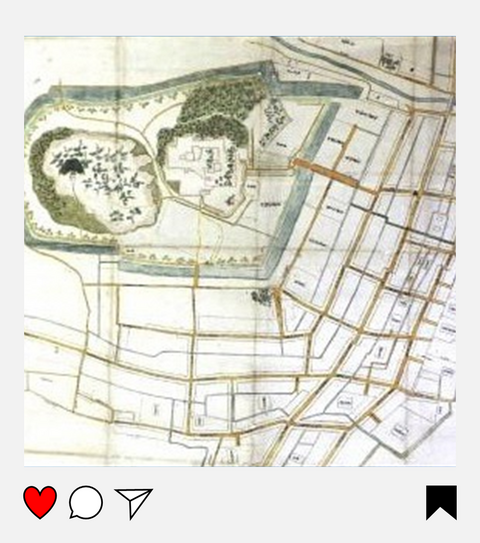

The other thing I notice when I’m strolling around the castle is the skill involved in planning it all. Matsusaka Castle Ruins aren’t just the stone walls, the structure itself is a must-see! When you take a look at the “Domain Map” (basically like modern blueprints), you can infer just how solid the castle was. The north side is built against the Sakanai River for an advantageous natural defense, and there’s gate after gate (well, there used to be) blocking progress through the inner castle, watchtowers (again, used to be) to counter enemies trying to get through the gates—pretty impressive defensive power. When I walk through and think about trying to attack the castle, I lose track of how many places I’d be beaten. If I managed to make it to the main tower, my forces would be in tatters.

Can We Get Some More General Information, Please?

Sorry, sorry. I just get very excited talking about all this. We’re already far in this article, but here’s some info for folks who aren’t into all the deep specifics about the castle.

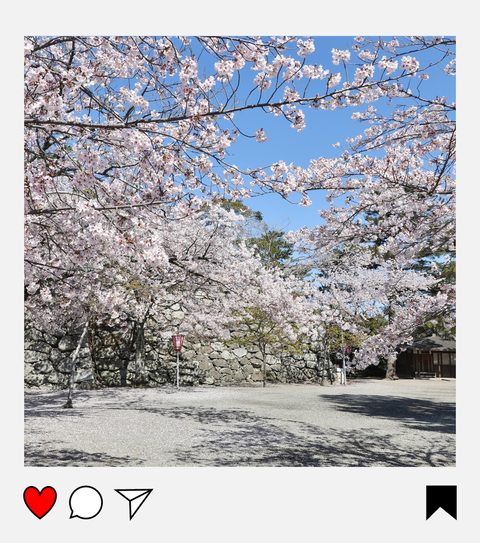

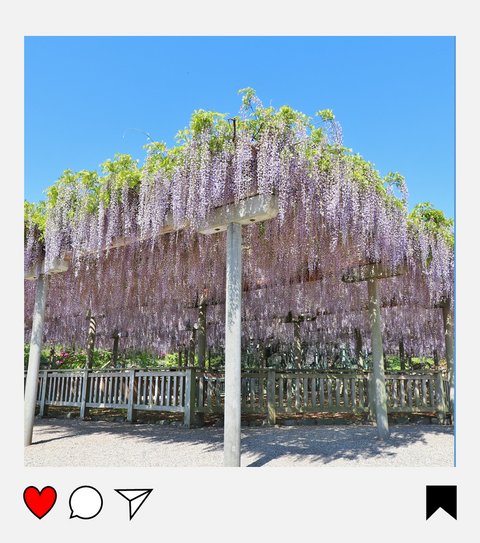

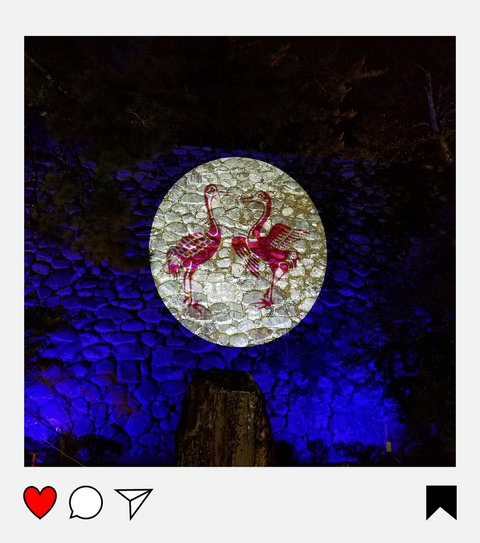

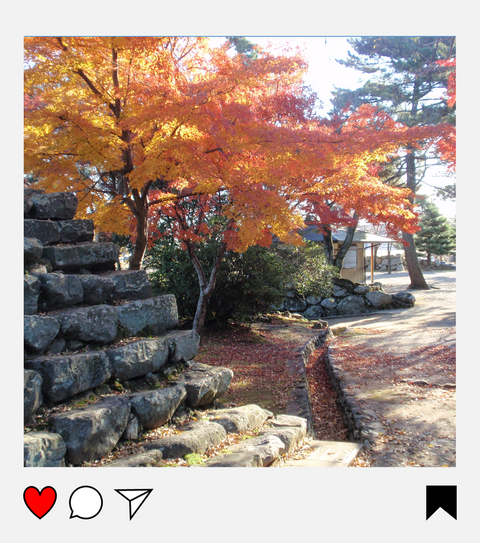

The Matsusaka Castle Ruins are now “Matsusaka Park,” and famous as a place where in the spring, people can enjoy over 300 cherry blossom trees, most of which are Yoshino cherry trees. It’s lit up at night, and many people visit. After cherry blossom season, the wisteria trellis in the second bailey is in bloom, and we have lots of people coming to see. Summers are green, and you can see autumn colors in fall. And if you’re lucky enough to visit when it snows, the views are second to none. The fact that you can enjoy something different every season is part of the charm of Matsusaka Castle.

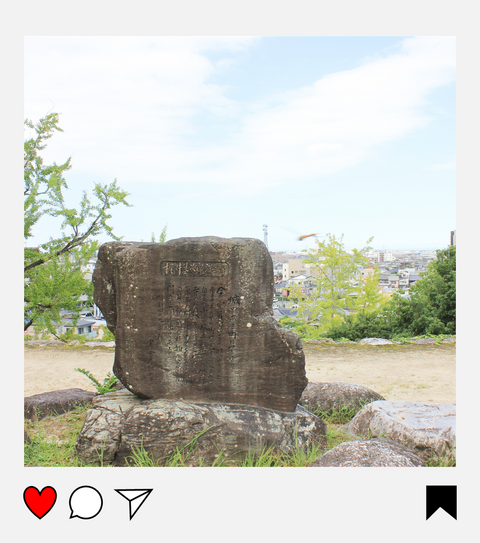

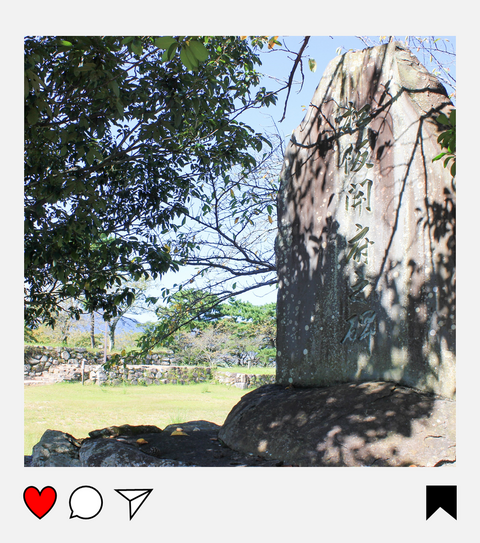

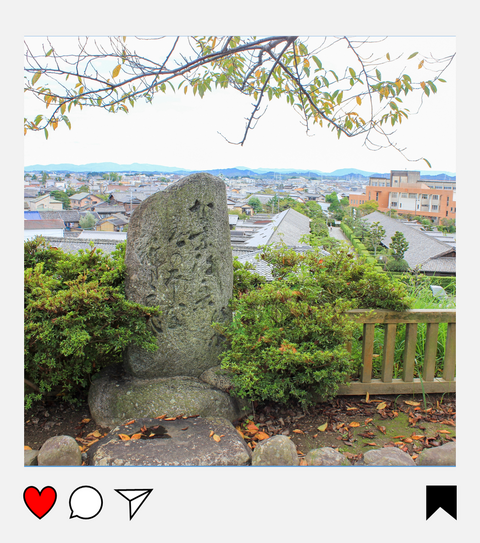

Other than that, there are a total of 12 stone monuments (some literary, some with poetry), and it might be fun to find them.

This year (2021) is the 10th anniversary of the Matsusaka Castle Ruins being designated a National Historic Site, and the 15th anniversary of it being included in Japan’s list of 100 Best Castles. If it weren’t for the pandemic, I’d be promoting castle tourism more. But, we’re also taking this as an opportunity, and we’re in the process of making new promotional items! If you’re interested, be sure to check them out!

There are plenty of other spots that I’d like to recommend in the area around the castle, but I’m going to end here for now. I’ll introduce more stuff next time.

Many thanks, from the Person Behind the Instagram.

For the latest, follow us on Matsusaka City Tourism Information’s official account (@discover_matsusaka)!

Recommended Spots Around Matsusaka Castle Ruins

Castle Guard Residences

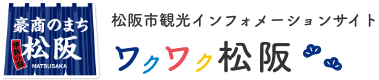

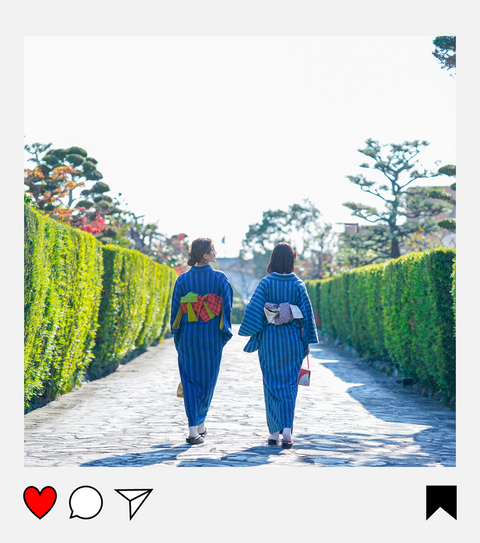

These are the homes of the 20 warriors (the Matsusaka Castle Guard) charged with defense of the castle, and their families. It’s the largest existing example of Edo period warrior residences, and the descendants of the original guards are still living there today. It’s one of Matsusaka’s most photogenic spots, and was a filming location of a certain famous movie, that it was.

Information on Visiting the Castle Guard Residence

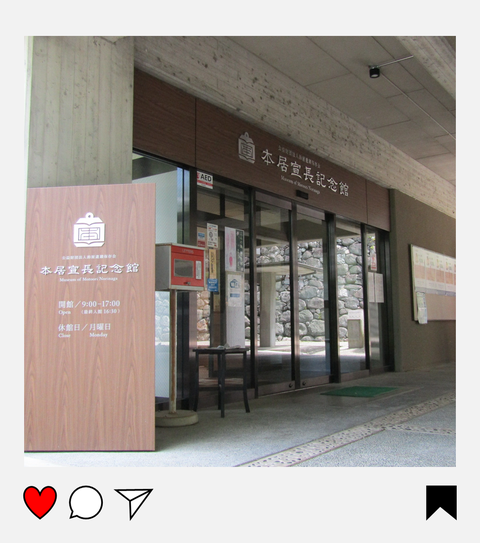

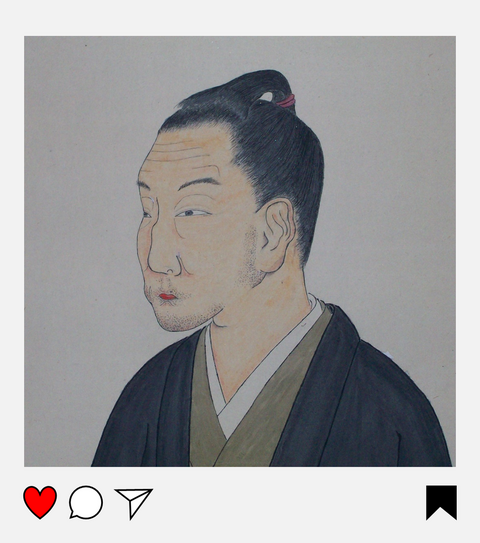

Motoori Norinaga Memorial Museum

This is the memorial museum of Motoori Norinaga, a famous scholar of Japanese classic literature. The original, handwritten manuscript of his major work, “Kojiki-den” (a 44-volume commentary on Japan’s ancient collation of myths and traditions), personal keepsakes, and a self-portrait are among the things on display, and the collection holds over 16,000 items. Next to the memorial museum is Norinaga’s Former Residence (Suzu no ya), and which includes a Japanese garden.

Motoori Norinaga Memorial Museum

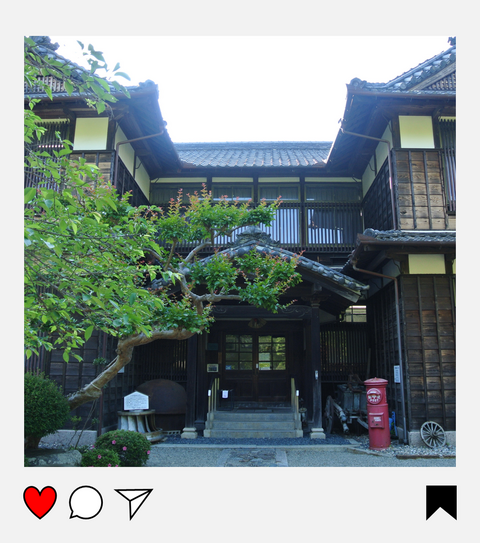

Matsusaka City Museum of History and Folklore (2nd Floor: Ozu Yasujiro Memorial Museum)

The building housing the Museum of History and Folklore is National Registered Tangible Cultural Property. The 1st floor has exhibits about the Matsusaka Castle Ruins, Matsusaka cotton, and Matsusaka history. The 2nd floor opened in April, 2021 as the Ozu Yasujiro Memorial Museum. The world-renowned film director Ozu Yasujiro lived in Matsusaka from the ages of 9 to 19.