The statue appears from nowhere.

In the western part of Matsusaka, the roads are picturesque countryside—mountains rise in the distance, the forests and valleys are punctuated with tiny villages, passing glimpses of stone bridges and emerald rivers.

And deep into the hills, coming around an unassuming bend in the road, I’m greeted by a giant Buddha-like statue in the distance.

Mizumoto-san, one of the leaders of the local residents’ committee who built the monument, gazes down the road as we talk.

“The people in this region are aging, and the population is decreasing rapidly,” he says. “There was nothing to appeal to tourists.”

Nigaki Town is along the Ise Honkaido, a road people historically travelled on foot. But recently, with more people moving to urban centers, many small towns like it are growing quieter.

“In this area, there are few children…more live nearby, but in this area, there are few elementary school kids, few middle school kids. You don’t often hear the voices of children.”

But for the past six years, the Nigaki Revitalization and Creation Executive Committee have strived to bring life back to the area.

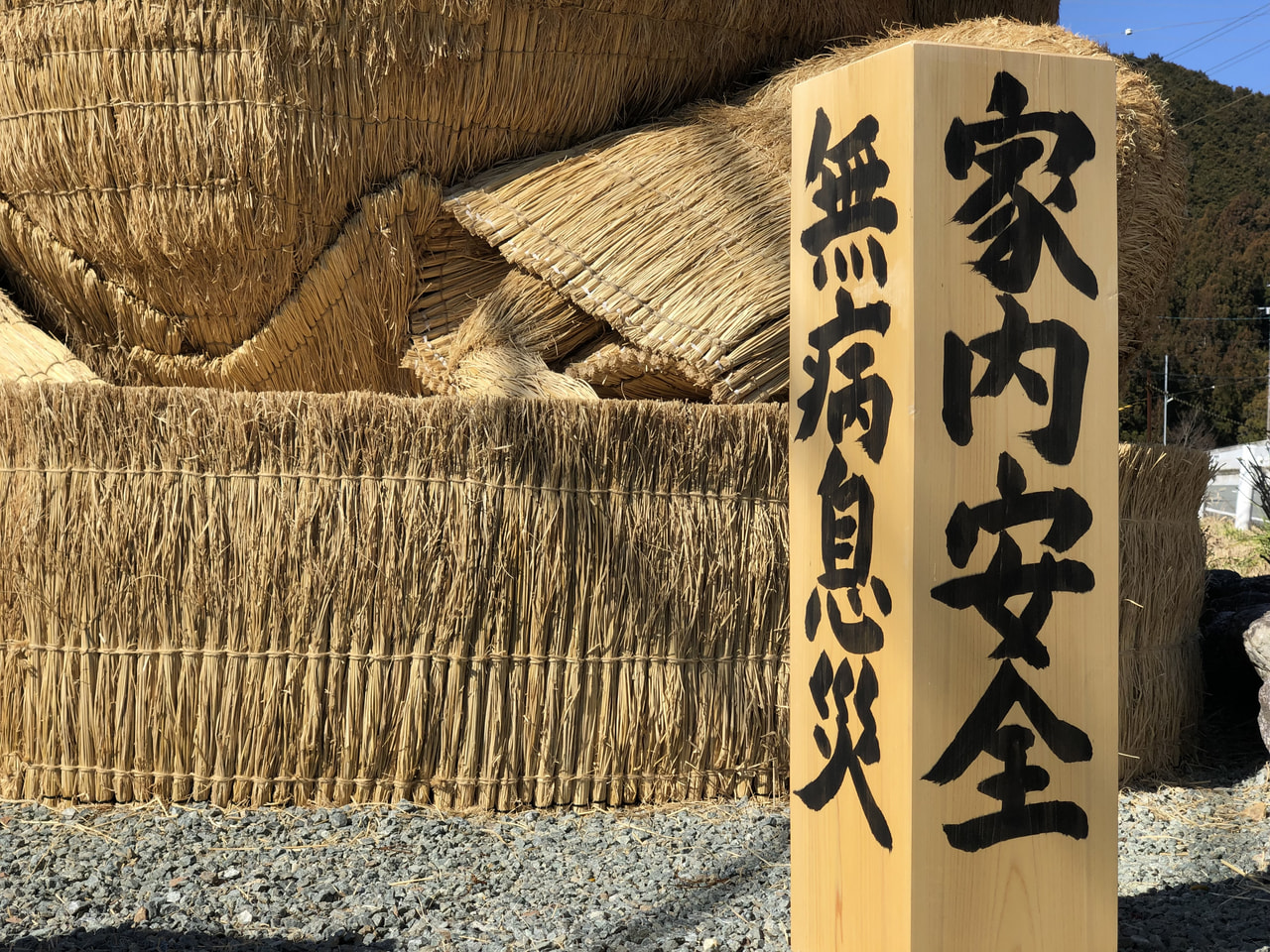

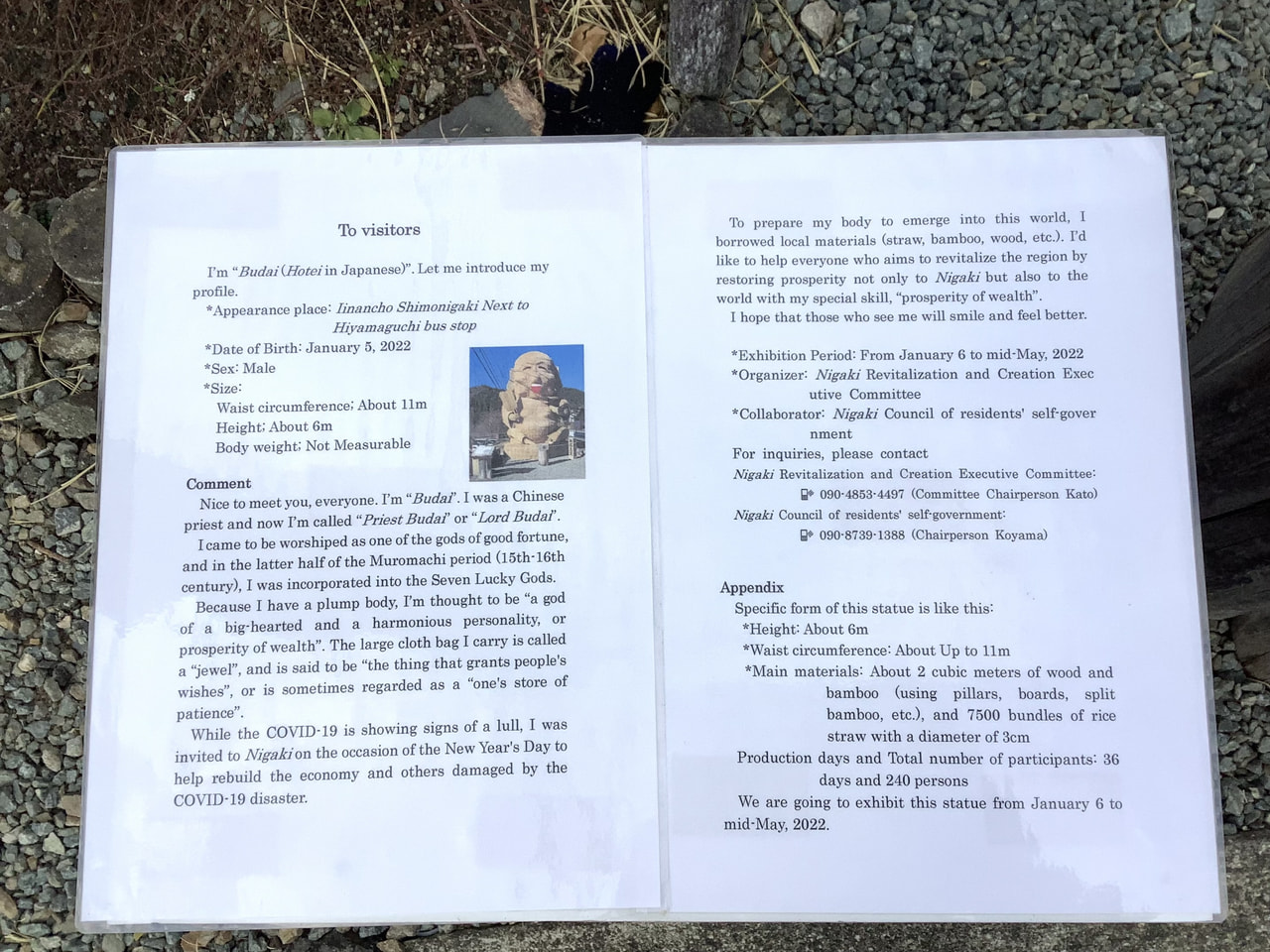

The six-meter sculpture of the monk Budai—Hotei in Japanese—is part of their annual effort both to bring people to Nigaki, and create a place to interact.

“As the population decreases and folks in the area get older, there’s not as much going on,” Mizumoto-san says. “And while this is here, even if it’s just for a little bit, having people stop by and take a look—that’s what got us started.”

And the statues have been a hit. People drive out to create photos, they’ve been featured in local news, as well as media networks outside Mie Prefecture. Mizumoto-san said a friend in Hong Kong even saw it in a local magazine.

Momentum picked up in 2020, when the group made an amabie—a Japanese mermaid associated with preventing epidemic disease.

“There’s a flow with the amabie from 2020. Since Hotei is a god of prosperity, it’s dual. One is so people don’t come down with COVID, but two, so the economy will get better.”

As we’re standing there talking, it’s clear the statue has brought an energy to the space—a number of people stop for photos: a motorcyclist, a pair of men in suits with SDG lapel pins, a group of four women who stay and chat.

Mizumoto-san tells me when they started, people asked “Are you going to do this again?” But by the third year, the question became “So, what are you making next year?”

“When we get people coming and saying ‘Wow, great job! This looks great!’ Hearing those things when people come to see, it means more than anything. It makes me think ‘Let’s do this again next year!’ And honestly, it’s that simple for us.”

Mizumoto-san, along with fourteen other council members, spends his weekends and free time creating the monument every fall.

They source area lumber, use bamboo from nearby forests, build the statue’s exterior with local rice straw. When the sculpture comes down around May, they save the lumber for next year, and give the straw to vegetable gardens, and farms for feed and bedding.

“That first year, even though I was appointed leader, there was a moment when we were thinking: How do we make this?

“And over the years, everyone began to come up with techniques. How can we make it better? How can we make it faster? Everyone studied. And before long, we got excited about it.”

I wonder about the team dynamics—especially with a group so large—and ask if they’ve had any disputes among the members.

“Not at all. Everyone knows exactly what they need to do.”

If anything, the little bit of difficulty the group encountered has all been technical.

“Parts of the statue that bend, acute angles. Sleeves, hands. That’s the hard part. And the bag in the back.”

Mizumoto-san shows me aspects of the statue I would have overlooked: the detailed hands and arms, the fact that the robe has inner and outer sleeves, the smooth way Budai’s bag starts at a single point and gradually gets wider.

“We focus on doing things carefully and thoroughly,” he says. “If you focus on care and thoroughness, things will turn out right.”

Every year, the group keeps their plans a secret. They make no announcements about the statue—they don’t even tell their families what they’re making.

The secret keeps people coming back to watch the progress, it keeps people from getting an image in their head before the statue is completed.

Mizumoto-san laughs when I ask him if he’s thought about next year.

“I’m just relieved we got this guy done,” he says. “I haven’t thought about next year!”

Several members of the group stand around chatting easily, comfortable in the space. One of them circles the monument with a pair of scissors, checking for imperfections, snipping loose straw. A passing car slows to catch a better look.

So, I ask, what’s in Budai’s bag?

He gives a slow smile.

“Everyone’s happiness,” he says. “Their prosperity.”

Visitor Information

The monument is generally on display from late December to mid-May the following year.

Accessible by car from National Highway 368. Parking lot available.

Cash donations accepted in a box in front of the monument.

The group also wrote an explanation in English! Read more below:

For those interested in more photos and a different perspective on the straw sculpture, check out the Japanese version of the interview!